Luscious photos and engaging stories sell cookbooks. But most people still buy cookbooks for the recipes.

A recipe is a road map that takes the reader from point A to point B. Sometimes it’s a quick trip to the store, a no-frills recipe for roast chicken or mashed potatoes. Maybe it’s a long excursion, fermented kimchi, salami or a tower of cream puffs called Croquembouche.

To continue the travel metaphor, there are many routes you can take. And there are many modes of transportation too – on foot, on a bicycle, in a car or on a sailing schooner. For each type of culinary journey, there is a recipe that meets its needs.

Some people use recipes when learning to cook. They seek solid instructions to ensure that they get from point A to point B. Solid recipes teach them how to cook, how to work efficiently and how to prepare a meal on time. Others read recipes like novels. The recipe writer is a storyteller using recipes to explore a culture. (See Honey from a Weed by Patience Gray.) The writer may use words to suggest how a dish is made. Recipes might not include measurement ingredients. Other recipe writers spend many pages of text explaining each step and nuance in how to achieve the same results in a recipe as they do in their professional kitchen. (See Judy Rogers recipe for Roast Chicken with bread salad, a classic.)

Writing recipes is a skill and art, one that you can master with practice. Here are some pointers for achieving clear and engaging recipes. Entire books have been written on this subject. These are the bare bones. (This is another post on the mechanics behind cookbooks. More on the artistry in future posts.) And this post is directed at recipe writing for home cooks. Writing for a professional audience has other considerations.

In recipe writing, clarity, content and personality count. A professionally-written recipe ensures quality results. It is standardized so anyone using it can understand the recipe and craft a delicious dish or meal. The greatest compliment a cookbook author can receive is that the recipes work.

Parts of a Recipe

Most recipes include the following components:

- Title

- Ingredient List

- Portion, Yield or Number of Servings

- Procedure, Method or Steps

- Headnote

- Notes, Features and Sidebars

Title

Think of a recipe title as a greeting. It give the reader an idea of what’s to come.

Craft titles that are descriptive not flowery.

Maple, Buckwheat and Nut Granola

Nashville-Style Hot Chicken Sandwich

You know what to expect from these two recipe titles. Maple syrup in granola with some kind of nuts and the less common ingredient buckwheat, should intrigue a granola fan. Nashville-style hot chicken is well known by now. If not, the words “hot chicken” conjure an aroma and taste. Dorie Greenspan is the queen of inviting recipes. Key words she uses in her recipe titles evoke a response in the reader, “I want to make that.” “Subtly Spicy, Softly Hot, Slightly Sweet Beef Stew” and “So-Good Miso Corn” hint at what to expect. You start salivating and are curious to read on.

Some words like molten, rustic or sleek, are descriptors that alert you to experience you’ll have seeing and tasting a dish. They add to the recipe’s appeal.

Avoid vague titles. “Uncle Joe’s Meatloaf” means nothing unless you know Uncle Joe. “The Best Banana Cake” sets up a contest with your reader, who is primed to judge not enjoy your recipe. The same holds true for other superlatives – marvelous, super, extraordinary. With those words in a recipe title, it had better deliver.

Ingredient List

When writing recipes, make things simple for your readers.

List the ingredients in the order in which they are used in a recipe. Simple? Many people often forget this basic step.

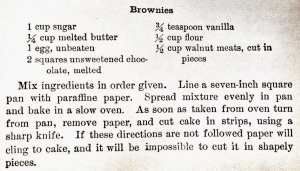

Cups, teaspoons, ounces, grams, it does not matter as long as you use a consistent measurement system throughout. And be sure to decide ahead of time whether you will abbreviate or spell them out.

1 teaspoon salt

1 tsp. salt

Salt, 1 teaspoon (uncommon)

These are three ways of expressing the same thing. Pick one style and stick to it. I like to see the measurements spelled out. There is no room for confusion this way.

The Brownie recipe pictured here comes from The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book AKA Fannie Farmer published in 1929. We credit Farmer with standardizing recipes by using a consistent measuring system – cups, teaspoons. (The notion that cups are accurate seems quaint; many cookbook authors, me among them, recommend weighing ingredients especially when baking.)

Use the generic name for an ingredient not the brand name unless you think that the brand matters. For example, 1 cup of bittersweet chocolate chips not 1 cup Hershey’s chocolate chips. (More on this in another post.)

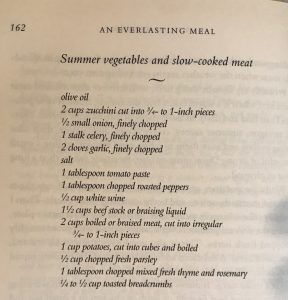

Many ingredients need preparation before they are used or measured. Garlic cloves, carrots, mushrooms or onions for example. Where you place the preparation effects how much of an item to use. Directions like “chopped” come right after the measurement if you are measuring them chopped.

1 cup chopped mushrooms

If you measure something whole and then chop it, you say:

1 cup mushrooms, chopped

Want to see why?

Try this exercise. Fill a measuring cup with mushrooms. Count the number of mushrooms. Then chop those mushrooms. Place them in the measuring cup and take note of how full the cup is.

Portion, Yield and Number of Servings

Everyone likes to know how much a recipe will make. A family of two might welcome a recipe that makes a quart of soup but one that makes 6 gallons would be a burden.

You can express how much a recipe makes in several ways.

Portions = 6 Servings, 1 Cake

Bulk quantity = 1 Quart, 2 Cups

Indicating the number of servings a recipe makes is good for a soup, stew, entrée and the like. Listing a bulk quantity is good for things like sauces and soups

Procedure, Method or Instructions

For decades, the late great Gourmet Magazine followed a unique recipe writing style. The method for making the recipe and the measurements were all rolled into paragraphs. (This style dates back centuries but fell out of use in the 20th century.) Look at this recipe for Käsetaschen-Cheese Canapes from a book published by Gourmet. Is it easy to read? How much Cheddar cheese do you need to make this recipe?

Kasetaschen CHEESE CANAPES

WORK INTO a smooth dough 1/2 cup softened butter, on 3-ounce package cream cheese, and 1 cup flour. Roll out the dough 1/4 inch thick, chill it for 30 minutes, and cut it into 2-inch rounds. Place a sliver of Cheddar cheese on half of each round, fold over the other half, and press it down well. Bake the rounds on a buttered baking sheet in a moderately hot (375F) oven for 10 minutes, or until the cheese is golden. Serve them at once.

Today most cookbooks, web sites and magazines require a clearer writing style. The procedure, method or instructions are written in separate often numbered steps. If they are not numbered, the steps are broken into separate paragraphs.

Recipes are written this way to make them easier to follow.

To write easy-to-follow recipe instructions:

List the steps in the order in which they must be done to make it easy for your reader to produce the recipe.

- You preheat the oven before starting to roast a chicken for example. (But you might not turn the oven on until later when making a yeast bread dough, which needs time to rise.)

- You grease the pans before you begin to make a cake batter, so the pan is ready the minute the batter is whipped.

Always suggest what heat to use.

- Simmer the sauce over low heat.

- Fry the vegetables over high heat.

Always ask yourself, what is useful to know. Think about your reader. What questions might they have when preparing the dish. They appreciate this.

Tell the reader what to look for when cooking and baking. For example, cook the potatoes until golden brown and softened. Simmer the stew until the sauce is reduced by half and coats a spoon.

Finish with serving instructions. A note about storing and how long a recipe keeps is usually well received.

You’ll make friends and gain their respect when you think about your reader at every step.

Headnote

A headnote is the introductory text after a recipe title. Think of this as your recipe blurb, like what you’d read on the inside flap of a book jacket. The headnote tells a recipe’s story. Here is where you can inject personality and humor. Perhaps there’s a tricky step you need to describe or an ingredient substitute to mention. Headnotes are where you’ll do this.

Only after I’ve made a dish a few times do I know what to emphasize in a headnote. And even though headnotes appear first, I like to compose them after I’ve written the recipe.

The only things that can be copyrighted in a recipe are the words. Surprising? I thought so the first time I learned this. It’s best to spend some time on the headnotes because they are such an important component of a good recipe.

When I teach recipe writing to the public and in my Food Writing class at Gateway Community College, headnotes take up at least one or more sessions. They could be the subject of an entire course.

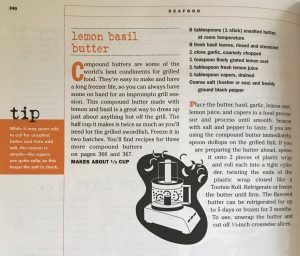

Notes, Features and Sidebars

Notes, features and sidebars are the important extras you’ll find in books and magazines. Some are essential; notes may be used to highlight substitutions in an ingredient list, or to mention a source.

Others are optional; length of cooking time or icons indicating seasonality are nice features but not essential.

Sidebars are different from headnotes. Sidebars are good places for information tangential to a recipe. For each type of cookbook, there are natural types of sidebars. Your book of Tuscan recipes might include sidebars about local lore or the history of the classic dishes you’re featuring. Your book on cooking with kids might feature interviews with kids who enjoy cooking each recipe.

Know that a cookbook author cannot dictate features and sidebars. The publisher, whether for a book, magazine, or website, determines what works. With the author’s input of course.

Common Mistakes in Recipe Writing

If you read cookbooks, online recipe articles and share recipes, you are probably comfortable with the basics of recipe writing. But even experienced cooks make some of the following mistakes:

- Ingredients not in the order in which they appear in the recipe.

- Instructions are not in a logical order.

This is easy to fix. Start by quickly writing down everything it takes to make your recipe. A brain dump. Then go back and re read what you’ve written. Put it in a logical way, the way you need to make the dish. If you make lasagna with homemade tomato sauce for example, you need the sauce before you can assemble the casserole. Start with the steps for making the sauce.

- The same ingredient is described using many different words.

Stuck when writing your recipe? Consult other cookbooks or reputable online recipe sites. Look at how they handle the complexities of your subject such as making pasta dough and cutting it into sheets for lasagna or carving a chicken. For lists of well-written cookbooks to consult, look at the list of winners of prestigious cookbook awards among them those given by the International Association of Culinary Professionals and the James Beard Foundation.

You can learn a good deal about recipe writing from many web sites including Food52, Bon Appetit, Saveur Magazine, Better Homes and Gardens and many more.

TRUC of the trade

I always consult at least three sources when researching anything.

Anything.

Be careful when you are adapting another cook’s recipe for publication though. Make the recipe your own. Test it and change it. Make the words your own. Think of this effort as you would any kind of research. Look at the word choices the recipe writer made. Ask yourself whether the recipe writer does it exactly as you do. Inject your own style into the writing.

In my next Cookbooks 101 post, I’ll write about how to make a recipe your own.

Want More?

Sign up for my newsletter for recipes, tips and to learn about upcoming classes and events. It comes out 1 to 2 times per month.